– Uma Maheswari Brughubanda

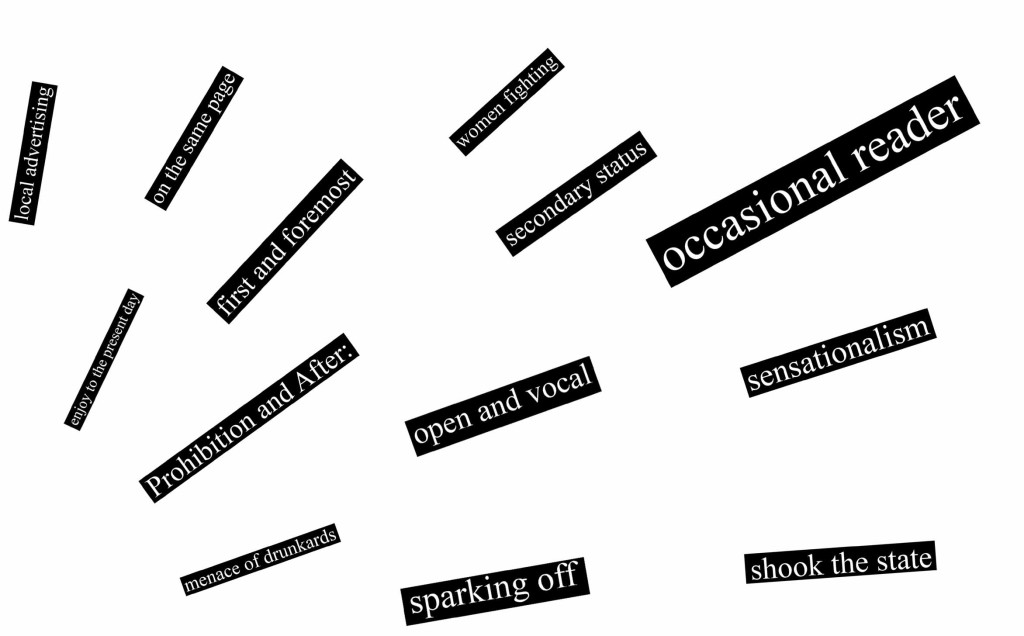

Eenadu, the largest circulating Telugu daily in Andhra Pradesh, played an unprecedented and sensational role in the anti-arrack movement that shook the state a few years ago. When some inspired neo-literate women in Dubagunta village in Nellore district attacked the excise jeep bringing arrack into their village, thus sparking off the anti-arrack movement in the state, Eenadu was the first newspaper to report the incidents in its Nellore district tabloid.

This essay is an attempt to (a) examine Eenadu’s history as a regional language newspaper and (b) to document the role that it played in the anti-arrack movement and subsequently in the struggle for prohibition. I have also tried to reflect upon the effects that the paper’s coverage had upon the struggle.

It is quite evident from the self-congratulatory articles in the Eenadu Sameeksha that the newspaper’s self-image is that of a social and political crusader. In one of the articles, Ramoji Rao is quoted as saying that what mattered was not mere reporting but the role Eenadu played in solving political and social problems. The paper also claims to have played a major role in different people’s movements like the literacy movement, the consumers’ movement, the prohibition movement and the savings movement.

The anti-arrack movement undertaken by rural women in Andhra Pradesh in 1992 was unprecedented and unique among social movements. Although women in Andhra had participated in anti-arrack agitations in the 1920s and 30s which were part of the Gandhian agenda, there had never been a sustained grassroots movement by women against arrack. In the 1930s a combination of several factors contributed to this struggle. One major reason [for the 1992 agitation] was the active promotion of arrack by the state government in an effort to augment its revenue. In Andhra Pradesh the state government has a monopoly over arrack production. In AP the excise revenue has been much higher in comparison with all the other states in India. However, as K. Ilaiah argues, in addition to the state revenue “there is an unstated income which works out to 2500 crores per year. For every 25 paise that the state gets, the contractor gets 75 paise. Part of this huge amount gets back to political parties in the form of party funds’. The increased alcohol consumption was concentrated in the rural areas. This meant that the poorer sections were spending on arrack much more than they were earning. This in turn meant an increase in violence against women, hunger and starvation in the family, and lack of education for children.

The anti-arrack movement undertaken by rural women in Andhra Pradesh in 1992 was unprecedented and unique among social movements. Although women in Andhra had participated in anti-arrack agitations in the 1920s and 30s which were part of the Gandhian agenda, there had never been a sustained grassroots movement by women against arrack. In the 1930s a combination of several factors contributed to this struggle. One major reason [for the 1992 agitation] was the active promotion of arrack by the state government in an effort to augment its revenue. In Andhra Pradesh the state government has a monopoly over arrack production. In AP the excise revenue has been much higher in comparison with all the other states in India. However, as K. Ilaiah argues, in addition to the state revenue “there is an unstated income which works out to 2500 crores per year. For every 25 paise that the state gets, the contractor gets 75 paise. Part of this huge amount gets back to political parties in the form of party funds’. The increased alcohol consumption was concentrated in the rural areas. This meant that the poorer sections were spending on arrack much more than they were earning. This in turn meant an increase in violence against women, hunger and starvation in the family, and lack of education for children.

In the northern Telangana districts, the CPI-ML groups, including the People’s War Group (PWG) have been agitating against arrack and liquor since the early 80s. However, in Nellore, Chittoor and Kurnool districts, it was the literacy programme, Akshara Jyothi that brought many rural women together. It was these neo-literate women who resolved to fight against arrack. It must be noted, however, that the science forum Jana Vignana Vedika played an active role in the spread of literacy. The women in most villages formed groups which physically prevented men from going to the arrack shops, publicly shamed arrack contractors and sellers, attacked liquor shops, set fire to the arrack barrels and sachets, and prevented auctioning of arrack shops. In Nellore alone they stalled auction sales 36 times. This is true of all district auction counters. As a result many women have been arrested and police have filed false cases against them. The women involved in the struggle were up against a powerful nexus involving the excise officials, the police and the arrack contractors.

News Coverage

In April 1992, Eenadu carried reports of women fighting against arrack in the villages of Ayyavaripalem and Saipeta. Eenadu is said to have been instrumental in the spread of the movement to a number of other villages through its extensive reporting in the district tabloids. By June 1992 the movement had spread to many more villages in Nellore district. However, until July of that year most of the reporting was confined to Nellore. After the first news item on 18th July Eenadu began extensive coverage of the anti-arrack movement between October 1992 and April 1993

In October 1992 the paper started a special page on the anti-arrack m ovement titled “Saara pai samaram” (The war against arrack). This page was devoted entirely to reports on the progress of the movement, the responses of various political parties, activist groups, the reports of deaths due to illicit liquor and so on. But significantly the reporting of the anti-arrack movement was not confined to the saara page alone. It occupied a conspicuous place on the front pages, in the city editions and in the women’s supplement Vasundhara as well. I list below the kinds of reports and items that were part of Eenadu’s coverage in the six month long campaign:

ovement titled “Saara pai samaram” (The war against arrack). This page was devoted entirely to reports on the progress of the movement, the responses of various political parties, activist groups, the reports of deaths due to illicit liquor and so on. But significantly the reporting of the anti-arrack movement was not confined to the saara page alone. It occupied a conspicuous place on the front pages, in the city editions and in the women’s supplement Vasundhara as well. I list below the kinds of reports and items that were part of Eenadu’s coverage in the six month long campaign:

1. During this period several editorials including six front page ones carried constant exhortations to the people to keep up the struggle, and appeals and warnings to the government ban on arrack and liquor.

2. The regular political cartoon by Sridhar which appeared under the title” Idi Sangathi” was suspended. In its place Sridhar began a new series called’ Saaraamsam” (meaning “summary” but also punning on the word “saara” meaning liquor) which he vowed would continue until the government imposed a ban on arrack. This feature continued for the next six months until April 1993, when the ban was finally announced.

3. Deaths occurring due to illicit liquor and accidents caused by drunk driving were reported in great detail.

4. The statements made by the leaders of different political parties like the BJP and the TDP, by writers’ associations like Virasam, Arasam (both Leftist groups), the POW (Progressive Organisation for Women), and right-wing political organisations like the RSS in support of the anti- arrack movement were also reported in detail

5. In its women’s supplement, Eenadu carried interviews with women legislators seeking their opinion regarding the movement. In its film supplement carried a new feature “Saara pai Cine Thaaralu” (Film Stars Comment on Arrack). Religious leaders and religious organisations like ISKCON also issued statements expressing their support. Thus it was an astonishing range of people that Eenadu brought together to build a moral consensus against arrack and liquor. (As independent reports confirmed, the women in the anti-arrack movement did not see the issue as a moral one.)

6. Interviews with cardiologists, psychiatrists, neurosurgeons, gynaecologists and gastroenterologists, provided authoritative medical evidence against the consumption of liquor.

7. A news feature titled “Saro Kathalu” (Liquor Tragedies) was introduced. These presented moving accounts of individuals and families ruined by arrack and liquor. Most of these stories were about violence against women by their drunken husbands. “Pachani Samsarallo Nippulu Posina Saara” (Happy Families ruined by Arrack) [Eenadu 12 November, 1992] goes a typical caption. There were other stories which described the suffering of children working in liquor shops; lovers gone insane after drinking; murders and suicides committed in a drunken state; fathers who sold their children for liquor and so on. The paper also reported the release of a book titled Saara-Saro (Arrack and Sorrow) which was a collection of account of such liquor tragedies.

8. In the city supplement reports were carried of the increasing menace of drunkards in different neighbourhoods and public places like bus stands, railway stations, cinema halls. One report stated- “Local Trains Turn into Running Bars”. {Eenadu, 10 October 1992), another described how various public parks in the twin cities like Public Gardens, Indira Park and Sanjivayya Park have turned into places for sinful activities. -”Parkulu Kavuavi Papakupalu”( Eenadu 9 October 1992).

It is evident that Eenadu sought to present arrack and liquor as the main problem facing the people of Andhra Pradesh. Apart from the coverage of the movement, the paper also took upon itself the task of coordinating and guiding the activists and supplying paraphernalia like a flag, a pledge, slogans and songs. Eenadu regularly published slogans which it encouraged people involved in the struggle to use. It conducted poetry and drawing competitions with the anti-arrack movement as the theme. The newspaper also conducted a contest inviting its readers to design a flag for the movement.

These forums were aimed at bringing together the women involved in the struggle, activists and political leaders. On January 2,1993, Eenadu organised a huge gathering of all such forums in Hyderabad presided by the editor Ramoji Rao, attended by the Governor, the Chief Minister and leaders of different political parties. Significantly, this meeting was not called an anti-arrack meeting but a meeting to promote the struggle against liquor.

The courage and perseverance of the women fighting against arrack and the support their movement received from various quarters including Eenadu forced the Congress Chief Minister Kotla Vijaya Bhaskara Reddy to impose a ban on arrack first in Nellore district and subsequently in the rest of the state. Though the “Saara pai samaram” page and the “Saaramsam” cartoon were suspended in April 1993 following the announcement of the ban on arrack, Eenadu continued its campaign for total prohibition until January 1995 when it was finally announced by the new Chief Minister N.T. Rama Rao of the TDP.

Why did Eenadu do all this? What were the stakes involved? It seems as if the paper’s campaign for prohibition had a political as well as a business angle to it. Woven into the anti-arrack reporting and editorials were calls to bring in a government that would implement total prohibition. The movement itself is described as being born out of the agony of housewives. What is more interesting is the last section of the editorial, which suggests that the women have a secret weapon in the form of the vote with which they could oust a government that did not have the courage to announce total prohibition and bring in a party that would do so. This front page editorial was published alongside a report announcing the TDP’s support to the struggle for total prohibition. The message that was sought to be conveyed through this juxtaposition is too obvious to require elaboration. Total prohibition was the major plank upon which NTR fought and won his electoral battle. It will also be recalled that NTR insisted upon dramatically signing the prohibition bill within minutes of assuming power on 16th January 1995. Eenadu’s anti-liquor campaign is also rumoured to have had a business angle, directed as it was against a rival newspaper Udayam, supposedly sustained by the liquor trade of its proprietor Magunta Subbaramireddy. Interestingly Udayam collapsed in 1995 following the implementation of total prohibition.

The two achievements of the paper’s campaign on the struggle were:

a) To shift the scope of the movement from the village level to the state level. A team sent by Anveshi Research Centre for Women’s Studies to Nellore in October 1992 reported that the women engaged in the struggle were vehement in their decision to “ locate their efforts within their villages in order to retain control over the situation.” The slogan that had been popular during the struggle was “ Maa Uriki Saara Vaddu” (We don’t want arrack in our village).

b) To shift the focus from arrack to liquor. Many women activists have characterised arrack as a problem for poor rural women while the fight against liquor was more an urban middle class women’s problem.

What Eenadu successfully achieved was an erasure of the political, social and economic aspects of the struggle. The women in the anti- arrack movement were fighting for basic amenities like water, health care, and education even as they were fighting against arrack. Eenadu’’s coverage not only underplayed these demands but also simultaneously presented prohibition as a panacea to all the problems plaguing the people of Andhra Pradesh.

The day prohibition came into force in the state, the paper published an editorial describing the implementation of the dry law as a victory of the Telugu people. “This is the day when the tearful appeals of the Telugu daughters are being finally heard.” (Eenadu, 16 January 1995) While prohibition was in force the paper initially published reports of decrease in the crime rate alongside pictures of triumphant policemen and excise officials with liquor and arrack bottles seized through their raids. That year October 2nd, Gandhi’s birth anniversary, was celebrated as Prohibition Day. The Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu congratulated Eenadu for its “unforgettable” role in the campaign against liquor {Eenadu, 3 October 1995). In his editorial of 5th October Ramoji Rao advocated a ban on toddy as well, citing the increase in manufacture of illicit toddy as the reason.

A cursory survey of the Telugu language newspapers of this period reveals that Eenadu increasingly published reports of the failure of the government in implementing the dry law and increase in bootlegging. Interestingly, it was the newly launched Vaartha which now took up the cause of the women who were part of the anti-arrack struggle and termed the Andhra Pradesh High court ruling upholding the lifting of Prohibition as a “betrayal” of the promises made to the people. Exactly in what ways Eenadu distanced itself from the prohibition issue and justified the lifting of the ban would require a more thorough examination of the paper’s 1997 editions than has been possible here.

The Anti-Arrack Women

A study of Eenadu’s involvement raises several questions of a general nature about the relationship between women’s movements and their media representations. How does the media represent women’s struggles and the women involved in them? How are the problems and questions framed and articulated? How are struggles sought to be organised? How is their scope defined and demarcated? Most significantly, what are the vocabularies that the media draws upon in its representations? In one of his editorials, Ramoji Rao describes the movement as a “ sacred struggle.” He says that women who hesitate even to step out of their homes have come into the streets, reminding us of the days of the freedom struggle (Eenadu 2 October 1992). The figure of Gandhi and his strategy of non-violence are frequently invoked. But the movement was not at all Gandhian in character. More than one editorial is a direct address to Gandhi. Ramoji Rao condemned the PWG’s use of violence as part of the anti-arrack movement, stating that the women were fighting to keep their families intact. The implication was that this made their cause commendable, even legitimate, unlike the PWG whose motives were questionable (Eenadu, 24 October, 1992). He also repeatedly describes the struggle as having been born out of the women’s tears -”With hungry stomachs, tears flowing, the helpless womenfolk endure this sorrow” (Eenadu 30 January, 1993);“Our daughters are weeping copiously” (Eenadu 16 January, 1993).

At the same time the women are compared at different times to Satyabhama, Durga, Kali, and Draupadi waging a battle of Dharma to slay the demon ‘Sarasura’. However, this kind of vocabulary is not used by Rao alone but is deployed by reporters, by legislators and film stars as well. These women are repeatedly described as icons of purity and idealism who are entrusted with the task of cleansing the nation.

Several writers have pointed to the fact that the majority of the women involved in the struggle belonged to the Dalit and Muslim communities. “The village committees formed in different villages are invariably led by the women belonging to the poorer Dalit households.” However, the dominant images of these women deployed by the press erase the caste and class identities that overdetermine their lives, turning the category ‘women’ into a monolithic construct.

The twin images of the weeping, helpless and vulnerable woman clutching her ‘taali’ and the woman roused to rage and action with flowing hair, flaming eyes, resplendent kumkum and trident in hand are part of our everyday mythologies about Indian women. Given the pervasiveness of these vocabularies the questions to ask seem to be – whether they are really empowering, and whether anything is to be gained by critiquing them. What these images seek to do is to legitimise only those struggles which seek to keep the family intact or protect a woman’s ‘honour’ and which in no way challenge patriarchal ideologies. For instance the Eenadu editorials’ repeated emphasis on women’s tears and the family mask the multiple methods the women were employing in their struggle, such as attacking the contractors and excise department officials, destroying arrack shops, using household items like the broom and the chilli powder, refusing to cook at home, even threatening to divorce their husbands and confronting the goondas belonging to the liquor mafia.

Uma Brughubanda teaches at English and Foreign Languages University

umabhrugubanda@gmail.com![]()