-Chanthu S

There are a series of incidents relating to gender on the University of Hyderabad (UoH) campus which are taken up and discussed by “concerned” individuals, groups and organizations. I find this very notion of “concern” problematic. People who voice their concern have a wide range of ideas, preconceived notions and imagination—logical or illogical—informing their actions on sexual violence, sexual harassment and other gender-related issues. What makes me reflect on this issue is first, a series of incidents I have seen, heard and experienced in the University of Hyderabad campus; second, I was intrigued by the way the campus community handles such issues; and, third, I am puzzled by the mode of functioning of the Gender-Sensitisation Committee against Sexual Harassment (GSCASH) in UoH.

In my opinion, sexual harassment and gender issues apply equally to women, men and sexual minorities. Therefore, how do I understand a campus community which in most cases expresses its concerns only about issues related to women? Is it that issues related to men are taken for granted? Is there a scenario wherein sexual minorities are not accepted in the campus community? Is it because organizations in the campus believe that addressing women’s issues attracts more electoral votes (during Student Union elections)? Is it because gender issues and sexual harassment will be addressed only on the basis of the caste and class identity of the survivor? Is it because organizations and independent groups believe that issues outside the heteronormative gender order are fundamentally upper class issues? Is the campus community sensitive/reflective about the nuances of gender, some of which are mentioned above?

It is true that in the society we live, the agency of men in patriarchal oppression is more than that of women. There is indeed a long history of women’s victimhood under patriarchal oppression which had its agents as men more often than women and sexual minorities. However, it appears that the historicity associated with women’s suffering under patriarchy leads to an overlooking of both men’s oppression under patriarchy and oppression of sexual minorities. This blindness and amnesia, among other things, act against the articulation of the victimhood of men and sexual minorities under patriarchy. It tends to dominate a seemingly collective notion of “concern,” which in most cases is extended only to women-as-victims as it plays

out at physical and emotional levels. This is a framework against which many events in this campus can be placed. Moreover, if we look closely, the categories get more and more rigid over time. Thus narratives on domination of men and sexual minorities, even if they were ever articulated, are erased from history. Retrieving these narratives from the past thus becomes important and is a process. GSCASH as an agency for gender sensitisation should be sensitive to this missing element in the past practices of analysis of gender.

Against this background, how do we understand a campus community where the explicit is identified more easily than the inconspicuous? And what are the hurdles in the way of identifying the invisible agencies of harassment/violence within the institution of redressal of gender violence (e.g., GS CASH)? If we notice the pattern of formation of such laws and committees in history, most of them draw invariably from instances of violence against women. More often than not, only horrifying incidents of gender-related violence that pertain to a certain class-caste group attract the attention of the middle class media in contemporary India. It may result in enquiry commissions and Supreme Court verdicts, but, sadly, requires another horrific incident to revive the ‘discourse’ albeit without any deeper implications. This is repeated at a micro level in universities.

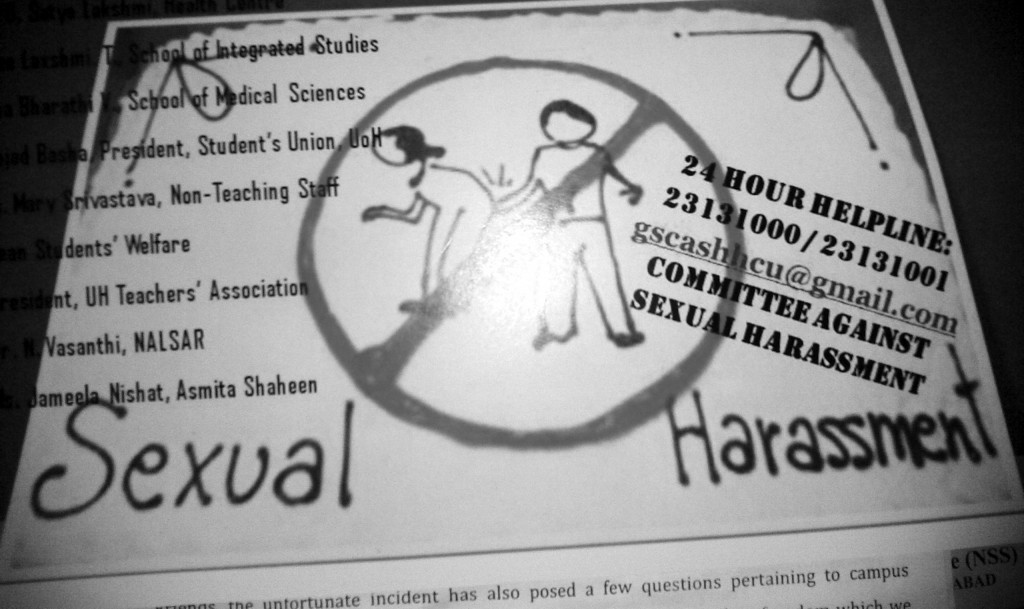

Let me explain, using an example, how a redressal mechanism disseminates gender-insensitivity to the extent that certain facets of the problem do not receive the concern it warrants. If we closely observe the sensitisation programmes of GSCASH (UoH) we find that the Committee itself is gender-biased and misleads the campus community. For instance, in July 2012, GSCASH came out with posters where “sexual harassment” was printed in yellow with the letters “men” in “harassment” in red (HARASSMENT). (Why was this red used for “men”?) This year, 2013, the Committee has come out with much more innovative posters featuring charts and images. The image in the 2013 poster has the figure of a girl bending down and a boy poking her from behind. This image is in the background of textual content on information related to sexual harassment.

Where then is the bias? The bias here is not with the poster but it is in the absence of posters which alert the viewer to modes of harassment other than those by men of women. For instance what about men and women ridiculing another man because he is feminine; or a woman because she is “boyish”? Why are posters addressing homophobia missing? Why is there only a male perpetrator here? The problem with posters of male perpetrator/female victim is that it reinforces stereotypes of the same. This image, though intended to sensitise the Campus, ends up confirming stereotypical imaginaries of a male perpetrator. Equally important in this context is the choice of the form of harassment displayed in the poster: Do only explicit forms of harassment/violence (and not covert forms of violence such as ridicule) inform the economy of popular imagination?

When I explain this all as an individual, I do not expect the institution to interfere with the choices I make with respect to sexuality, which are fluid in nature. On the one hand, there is enormous social pressure to maintain gender roles as is clear from the observation of the process of upbringing of an individual. On the other hand is the fluidity of sexuality which can be traced from the childhood itself and which is suppressed by the rigidity of gender discourse.

This fluidity makes it possible that an individual will encounter dilemmas at different points of one’s life in varying intensities. Therefore the interventions that an institution makes in this regard must be sensitive to these fluctuating realities. An individual therefore will never expect the institution to encumber one’s sexual choices. The enormous social pressure one might encounter at this juncture might stop a person in question from sharing and addressing these confusions. Under such situations, sensitisation programmes can act as an agency to break this silence without interference of individual choices.

Also to be kept in mind is the fundamental principle that in a case of sexual harassment, the redressal mechanisms must concentrate on the action and intention of the persons involved rather than their gender identities. This will ensure more objectivity and gender equality.

Other than introducing more security guards, surveillance networks and CCTVs we need proper sensitisation programmes which will initiate a healthy discussion on gender and sexuality on this campus. Since we are placed in a university system, awareness programmes and sensitising of the redressal mechanism itself should begin from the administrative level to the student community as well as to the teaching and non-teaching staff on the campus, thereby initiating a discourse on the equality of women, men and sexual minorities.

An environment should be created where the campus community is sensitised through different means like posters, slogans or wall paintings in public spaces. Also, rather than obstructing the freedom of movement of students at night by not opening night canteens, more night canteens should be introduced so that the administration and the student community will overcome the fear of harassment at night. It will definitely bring alive the public spaces in the campus. Such sensitisation programmes will definitely bring down the inhibitions to talk about gender, sexual harassment/violence and institutional homophobia. This will instil confidence among all the sections of the campus which come under the category of gender. This will create an environment in which anyone can live free irrespective of considerations of their gender, in a way that does not interfere with anyone’s individual choice.

Chanthu is a student at University of Hyderabad

When the law doesn’t recognize rapes of men and transexuals, this is expected. Women’s issues are also more fashionable.